Logline: As Afghanistan falls to the Taliban, retired veterans 7,000 miles away go above and beyond to keep their promise to their Afghan allies and airlift them to freedom.

Now That Should Be A Movie.

Short Pitch

It is called Operation Pineapple Express

It is a War Thriller

In the vein of Dunkirk

It is like Schindler’s List meets 12 Strong

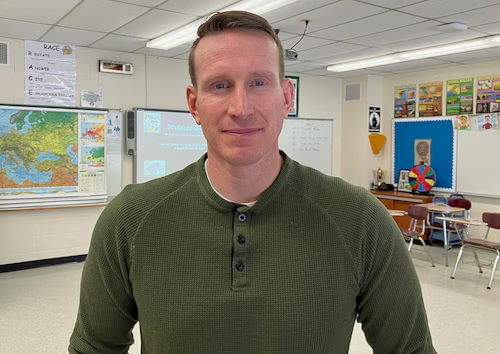

It follows Green Beret veteran turned playwright Scott Mann

And foul-mouthed Afghan intelligence officer Lieutenant Colonel Kazem

As they seek to escape and help others escape the Taliban during the American withdrawal from Afghanistan

Problems arise when the US government and top-ranking military officials refuse to respond to the humanitarian crisis unfolding outside the Kabul airport, allowing the Taliban and ISIS-K to block Afghans and even American citizens from reaching the safety of the U. S. base inside.

Together the American servicemen’s faithfulness and their Afghan allies’ bravery will overcome the obstacles blocking their way to safety and freedom.

The idea came to me during the dark days of August 2021 when reports of the heroic efforts of retired service members helping their Afghan allies escape shined like a bright light of hope.

My unique approach would be the clashing juxtaposition of retired service members in peaceful and prosperous America as they use modern technology to help their allies in tumultuous Afghanistan escape the Dark Age beliefs and behavior of the Taliban and ISIS-K.

A set piece would be when Scott Mann in Tempa Bay receives a message from his Afghan ally Nezam in the chat room Save Nezam. He has made it past the Talibs and paramilitaries blocking access to the airport. He needs a password to give Scott’s military contact on the ground. Scott contacts the military service member at the airport, asking him to come up with a password. The contact comes up with “Pineapple.” Scott ends the password to Nezam. Nezam approaches a servicemember on the ground. “Excuse me, sir, I am the pineapple,” he says. “You’re the pineapple,” asks the contact, verifying. Nezam answers in the affirmation. The contact lets him enter the airport, giving him directions to the processing center. Nezam sends Scott a message, “I am in.” Scott collapses to his knees on his driveway in Florida. His wife runs to him, thinking something is wrong. He looks up at her with a smile. “He made it, honey,” he tells her. Then he changes the name of the chat room to Task Force Pineapple. There’s more work to be done.

Target audiences would be men and women (30-70), military veterans and their families, military service members and their families, Afghan Americans, educators, activists, military buffs, history students, and war movie fans.

Audiences would want to see it for its themes of faithfulness, bravery, honor, endurance, steadfastness, devotion, courage, and overcoming as well as its thrill and excitement of a rescue mission during a momentous historical event

Introduction

Today’s book is Operation Pineapple Express: The Incredible Story of a Group of Americans Who Undertook One Last Mission and Honored a Promise in Afghanistan by Lt. Col. Scott Mann, from Simon & Schuster.

Like most Americans, I believed that it was time for the U.S. military to wind down its war in Afghanistan. As Charlie Daniels’ song said, “Let ‘Em Win Or Bring ‘Em Home.” But like most Americans, I was shocked by the humanitarian crisis that unfolded in August 2021 as the Afghan government collapsed. And, like many Americans, I was disgusted when our country’s leader, instead of following the example of President Obama’s response to the Islamic State’s genocide of the Yazidi at Sinjar just a few years earlier, said he would not ask our military personnel to make any more sacrifices in Afghanistan, then walked out of the room ignoring reporters’ questions about fleeing Afghans clinging to and falling from planes.

Then, like many of my fellow Americans, I was awed when many of those military personnel, both active and retired whom Biden said he would not ask to make any more sacrifices in Afghanistan, stepped up and made sacrifices in that country, keeping their promises to the fleeing Afghans and going above and beyond the call of duty as their government failed to do its job. Even as the news reported on these remarkable men and women, people were already saying “That should be a movie.”

It was searching for books that could serve as the basis for a post about a movie to honor my fellow Americans who stepped up during the fall of Afghanistan, and to hold our government accountable that led me to pick up Operation Pineapple Express by Scott Mann. While I apologize for my post having the word count of a novella, there was a lot I had to cut. From the heroic, like retired Green Beret Matt Coburn who interrupted his comfortable suburban life in Pennsylvania to directly contact government and military officials in charge of the situation at the Kabul Airport to hold their feet to the fire to get his Afghan contacts through the gates. To the fascinating, like Master Sergeant Basira Baghrani, the first female graduate of the Sergeant Major Academy, who was spared when the Taliban looked for her with a recruiting poster that had an image of her wearing glasses and did not recognize her without them because they had just been destroyed by the crowd surging around her at the airport. The heartrending, like Afghan Special Forces operative Bashir Ahmadzai kissing the ground of his homeland after his father told him via a cellphone call, “Get on the plane, son. We will find our way to you.”

I hope what I have included, which is necessary to tell the story of the Afghans and their American allies, substitutes for and honors all those whose stories unfolded around the Kabul airport that August.

ACT I

Beginnings (Pages 1-10)

The war in Afghanistan for America was over by 2017. After President Donald J. Trump gave the go-ahead to drop the MOAB – Mother of All Bombs – on an ISIS complex in Afghanistan, attacks on U. S. forces in the country virtually came to a stop. The reins were handed over to the Afghan National Army (ANA) and other Afghan forces, which had been doing 98% of the fighting for years

In 2020 Trump signed the Doha peace agreement with the Taliban. However, he makes the mistake of excluding the Afghan government or any coalition nations from the agreement. May 1, 2021, is the date set for a U.S. withdrawal from the country.

One of the Afghans to whom the Americans pass the torch is Nezam – Nezamuddin Nezami – a member of the Afghan Special Forces (SOF).

Nezam’s life has been marked by war. While an infant, he was nearly killed by a Soviet MiG bomb. As a teen, he saw the Americans and U.N. forces come to liberate the country from the Taliban. They looked like Sylvester Stallone in Rambo III. He faced conflict in his own family. He ran away from home to escape his abusive stepfather. “You’re a backpack man,” his uncle told him. “You carry your home with you.”

At seventeen Nezam joined the ANA in search of a home, wearing women’s high heels to meet the height requirement. Using similar antics he joined SOF, working side by side with the American Green Berets, whose motto was De Oppresso Liber – Liberate the Oppressed. He became part of the Village Stability Operations (VSO) which worked in remote villages, building relationships, creating vanguards for the Afghan government, and training local Afghans to fight the Taliban. The ultimate goal was for the Afghans to stand up for themselves without a massive US military presence.

Through VSO he formed relationships with “Mullah Mike,” a Georgia country boy who learned Arabic, studied the Quran, and married a Muslim woman. During training at Fort Bragg, a commando named Johnny Utah took him under his wing. Nezam would later save Johnny Utah’s life during an ambush in Afghanistan.

He also met Scott Mann, the leader of VSO. Scott had come to Afghanistan to avenge a friend from Ranger School killed on 9/11 at the Pentagon. He soon found he could not kill to victory. Instead, he turned to winning hearts and minds through village engagement.

Nezam gained the American’s respect by volunteering for every operation and patrol. The Americans dubbed him “Space Monkey” because of his agility and willingness to scamper onto rooftops and fix radio and satellite wiring. He had been shot in the mouth once and in his chestplate three times. As Nezam and the other Afghans fought side by side with the Americans a brotherhood was formed, and many Green Berets made a promise to see the Afghans through to victory and honor their service.

As the U. S. presence in Afghanistan began to dwindle, turning over command to the ANA, the Taliban increasingly targeted the best-trained Afghans, pilots, special operators, and judges. Scott encouraged Nezam to work for one of the U. S. contractor companies guarding Afghan infrastructure. Not only was the pay better, but it would make him eligible for a special visa program (SIV). Taking Scott’s advice, he got a job guarding a power plant.

He submitted his SIV application to the State Department on July 4, 2020. He learned in September that it was moving through the State Department. In the Spring of 2021 during a House hearing regarding 18,000 unresolved SIV applications a special envoy said they believed the Afghan forces would not collapse right after the U. S. withdrew. The Biden administration pushed back the withdrawal date to September 11, 2021, believing that the government of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani would stand strong.

But the reality on the ground was different. The Taliban was taking over the country, avoiding U.S. Military bases so as not to violate the Doha Agreement. Why hadn’t the withdrawal been in winter? Like in Biblical times, the Taliban rested in winter and began their campaigns “At the times when kings go forth to war” – Spring. By summer they were in full fighting mode.

By the summer of 2021, Scott Mann has settled in Tampa Florida. For years, he was haunted by the death of his friend Pedro, killed on a mission he approved. He was loaded with guilt over the death of a six-year-old girl who had not been in the area until after he cleared a bombing mission. In 2015 he sat in a closet with a .45 in his hand, unable to translate from the military and war to civilian and peace. Only the thought of his three sons kept him from pulling the trigger. He was now a playwright – a first for the Green Berets – hoping to use art and theater to bridge the gap between military personnel and civilians. He had given up doing TV interviews years ago.

In Syracuse, New York, Zac Lois, a Green Beret turned intercity social studies teacher has been trying for years to put Afghanistan behind him for the good of his family. But that has not stopped him from trying to help his former interpreter, Mohammad Rahimi, get out of the country for over a month.

Inciting Incident (Pages 10-15)

Meanwhile, Nezam has been receiving threatening texts from the Taliban for years, but they intensified in May. In mid-June KKA (Ktah Khas Afghanistan), the most elite of Afghan units surrendered after being ambushed by the Taliban, believing they would be spared. Instead, they and their leader were executed. Nezam texted Scott with the news. Stay Strong Old Friend, came the reply. Uh? He would not die for a power plant. He burned any papers that could identify his service with the Americans. He cannot burn the orders authorizing him to wear the blue and gold “long tab” emblazed with “Special Forces.” He looks up to see a neighbor, an old mujahideen, watching him. Nezam greets him by placing his hand over his heart. The old warrior returns the favor and shuffles away, his blessing given.

On June 22, Nezam is 350 miles from Kabul. He records a seventy-five-second-long video explaining what he has done for Americans and Afghans and asks for help. He needs a helicopter and wants the American government to send it. He shares the video with Scott, Johnny Utah, and other Green Beret friends.

In Florida, Scot sits on his porch overlooking the Alafia River, doing whatever it takes to get Nezam’s SIV approved. He uses the Signal app to contact his friend 7,000 miles away. Nezam sends him a photo of himself standing next to a Russian Mi-17. But who would fly it? The six thousand American aviation support contractors have already left the country. Fortunately, Nezam has a friend at the base who could fly the helicopter for a “gift” of a phone card.

After making it to Kabul, the next stop would be Hamid Karzai International Airport – known as HKIA. He would stay at his uncle’s house, keep low, and wear a COVID surgical mask as a disguise. Scott keeps running into bureaucratic red tape and snafus regarding the application. He receives a text from Nezam. I think the whole country is a month away from flipping.

On July 1 US forces hand Bagram Air Force Base over to Afghan Forces, including a prison full of thousands of Taliban. Soon afterward, the Taliban attack the base and free the prisoners.

A Green Beret major Scott contacted says because of Nezam’s time at Q Course, he qualified for a special exfil list of Afghans who had worked on behalf of SOF. The major asks for the SIV application so his political advisors could start working on it directly.

Scott let Nezam know. Nezam replied, “I feel like Anne Frank and there are Nazis everywhere.”

Scott calls Mullah Mike, who had worked with the CIA. Maybe he could pull some strings. He hated to drag himself and his family back into Afghanistan after so many years. But with events like the bombing of a girl’s school in Kabul, he and so many other veterans knew the war would never end for them if they did not honor their promises to their allies. He set up a network with other Green Beret veterans who were swapping messages about the stalling and failing SIV program and how to get their Afghan comrades out.

In Nimruz Province, Lieutenant Colonel Kazem watches as the Taliban rolls armored trucks into Iran. With no air support to call, he could do nothing. The governor who had requested his help in fighting off the besieging Talibs has fled. Now troops were deserting. The Taliban says individual soldiers could surrender, but men like Kazem, part of the Afghan intelligence services, will not be allowed to surrender. “We have something special for them,” the Talibs warn. His motto of “Life F—ing Sucks” is explicable right about now.

He thinks of Will Lyles, Green Beret with VSO for whom he had translated. He had helped rescue Willi after he lost both legs to an IED. Both legs for what?

On August 6th the provincial capital, Zaranj, becomes the first to fall to the Taliban. Kazem wires explosives through the armory of his base. The “motherf—ers” would not get his armory. As the base explodes sky-high, he leads his column of vehicles through the Taliban lines. The Talibs pursue in their vehicles. Kazem escapes with minor wounds to his wrists. This is no longer an insurgency but “a war of movement.”

On August 15 Nezam texts Scott that the Taliban is looking for him in Kabul. Scott sends him a voice memo to try to calm him. “We’re going to find a way to get you out.” Now Scott was not only handling a visa issue, but he had just made a promise impossible to fulfill.

Second Thoughts (Pages 15-20)

The streets of Kabul are jammed with vehicles and people. Banks close as people rush to retrieve their money. Radio stations call out Kabul districts as they fall. Talibs throw grenades at government buildings with no response from government forces. An Afghan government spokesman is assassinated in his car, proving that civilians will not be spared. Women with lipstick and no head coverings run to their apartments before they are spotted by Talibs. The day ends with the news that President Ghani has fled the country.

Secretary of State Anthony Blinken had said in June that a collapse would not be something that happened from a Friday to a Monday, believing they had months to prepare for an evacuation. Now literal dumpster fires of documents lined the embassy road known as Pennsylvania Avenue. Chinook helicopters fly staff three miles over the gridlocked city to the new embassy set up by the CIA at HKIA.

“The Taliban is not the south—the North Vietnamese army,” said President Biden on July 8th. “…There’s going to be no circumstance where you see people being lifted off the roof of an embassy in the—of the United States from Afghanistan.” He was partly right. As the US flag was lowered, folded, and stuffed into a canvas sack, Chinooks evacuated Americans from a soccer field on the compound.

On August 15, the 2nd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment – the White Devils – deploy at HKIA. Among them are First Sergeant Jess Kennedy and Captain John Folta, just appointed to his first company command.

Climax of Act I (Page 20 – 25)

In Syracuse, Zac texted Mohammad Rahimi to get his family and head to the airport. Rahimi takes his SIV application and Zac’s letter of recommendation, hoping they’ll be enough to convince the guards to let them pass. Outside the gates of HKIA, the Taliban brutalizes whomever they will. Husbands and fathers are helpless to defend their families against their blows. Men are randomly shot. One man is shot in the head close to Rahimi’s five-year-old son. He tries to turn him away from the bloody sight. Too late. He can see in his child’s eyes the trauma already setting in. They’ll try again tomorrow.

The crowd remaining outside the Concertina wire face a situation straight out of Sophie’s Choice. Captain Folta watches as a father has to decide between his children and his pregnant wife who has just broken an ankle. Folta tells the man he cannot make the choice for him, but if he were in his shoes he would never leave his children. The man and his wife climb back over the wire and disappear into the crowd with their children.

On the same day, American Apache Helicopters asks for permission to engage insurgents killing innocent people. The word comes back negative. The American fight with the Taliban is over.

Scott watches on the TV as a mob rushes and then bodies fall from a C-17 taking off from Kabul. Twenty years of fighting and dying for this? His youngest son would be leaving for college in just a few days. He should be proud right now. Instead, he was watching his government break its promise.

He texts Nezam and receives a reply that strikes him in the heart.

I’m not afraid of dying. I’m just afraid of dying alone.

That does it. Scott has made a sacred promise, and he plans to honor it.

ACT II

Obstacles / Subplots (Pages 26-40)

On a whiteboard, he writes in big letters SAVE NEZAM.

With Garth Brooks singing about friends in low places, he looks at a map of HKIA. The main approach to the airport from Kabul is South Gate. From there, going counterclockwise around the airport, there was Sullivan Gate, then Abbey Gate, which a sewage trench ran alongside. Next were East Gate, North Gate, Northwest Gate, Glory Gate, also called Liberty Gate, and West Gate.

He needs to get Nezam through an enemy-controlled city undetected, pass the Taliban perimeter around the airport, through a desperate crowd of thousands, present him to the American gate guards without him getting accidentally shot, and on a flight with an incomplete SIV.

He contacts Mullah Mike, serving at an undisclosed location in Europe. He has a friend who fought alongside Nezam now working as a special operations liaison to the intel agencies. He would help but needs to keep a low profile. The SIV issue was red-hot.

Scott needs someone with political clout who could cut through the red tape. He calls Congressman Mike Waltz, who he saved during a tour in 2007. Waltz suggests his executive assistant Liv Gardner, a military wife. She copes with her ADHD by multitasking and being obsessed with Afghanistan.

To keep in contact with everyone Scott starts a chat room on the app Signal, Team Nezam. They have a team. Now they need a plan.

On August 17 special envoy for Finland Jussi Tanner lands at HKIA with a list of Afghanis who had worked with Finnish forces that he needs to bring inside the airport. He watches as Afghan NSU paramilitaries, a CIA-sponsored special ops group, patrols the perimeter in their tiger-striped fatigues. American soldiers throw flash bangs and teargas to control the crowd and fire warning shots over its head. Sometimes American soldiers rush and grab someone from the crowd. Outside the wire, Talibs, their white flags flying from captured American armored vehicles, patrol the mob of thousands of dirty, thirsty, desperate asylum seekers, occasionally beating men with rubber hoses or shooting ethnic minorities. The mob crushes children and the elderly. It looks like Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa.

The chat room digitally cheers when a former USAID foreign service officer puts Nezam on a flight manifest. Mullie Mike messages the chat. “Taliban locking the airport down. He needs to haul ass to the airport now. If he waits, he’s dead. Hundred percent.” Scott sets up a separate chat for Mike to give instructions directly to Nezam. The whole process is like building a car while driving it down the road.

On August 18th, U. S. Army Major General Donahue met with the Taliban to discuss securing the perimeter. The Talibs secured the outer perimeter of HKIA, and manned checkpoints, dividing the crowd into male and female lines, to screen the crowds around the gate, and make sure that the Afghans did not overrun the airfield. The Americans, British, and other UN forces and allies would guard the gates. For now, ISIS-K was their common enemy.

Scott and his team will try to get Nezam through Sullivan Gate near the former CIA compound, the next day.

The morning of the 19th starts with no response from Nezam for a couple of hours. Scott texts him: Hey brother, contact Mullah Mike. In Kabul, Nezam steps out to his uncle’s car, the only place he can charge his phone due to the power outage. His screen floods with messages. Mullah Mike tells him to try the different gates, first Sullivan, then East, North, etc. Nezam hails a taxi and starts toward the airport. His phone battery is at 60 percent

Arriving at the airport he goes from gate to gate, staying on the edge of the razor wire. Flashbangs go off creating the kind of chaos that Nezam’s training thrives on. Arriving at East Gate he takes his chance, tearing through the mass of humanity. Suddenly he is down on the concrete, writhing in pain, a member of the NSU, AK-47 in hand, standing over him.

At an undisclosed European location, Mullah Mike emerges from a no-cellphones-allowed meeting. When his weak link connection allows him to read Nezam’s messages, he sees that he has made it to the gates but has no name or contact to grant him entrance. Mike begins making contacts, including the 8th Marines at East Gate.

The NSU thug moves on from Nezam to bully someone else. Nezam pulls out his phone and snaps a photo of the location so Mike can better assess the situation. Suddenly another NSU man is upon him, taking the phone away. Nezam says he was Special Forces. The tiger-striped man begrudgingly returns the phone.

The loudspeakers bellow with his name, “Nezamuddin Nezami.” As he struggles through the crowd and past the NSU, he feels someone pull his backpack, full of documents that could identify him, off his shoulder. He turned to see who took it, but they were absorbed by the crowd.

His phone was now at 50%.

In Tampa, messages start coming in around 4:00 in the morning. “He’s at East Gate.” Scott reads them and thinks about how it had been thirty minutes since the last note Nezam sent and twenty-four since his message in Team Nezam. Brutal math in the dead of night. Toward dawn, a message comes in from Mullah Mike: A Marine corporal is getting shit done because she picked up the phone and gave a f—.

At 7:38 Nezam texted: Two people died next to me. I’m just one foot away.

Nezam, thirsty, and missing his documents, is close to giving up. He helps move a dying man out of the throng, crushed against the pavement by the crowd, The Marines at the gate ignore his calls for help. Then he receives a message instructing him to take a selfie for near–recognition. He sends his ashen profile to the chat.

From their posts, Marines throw water bottles into the crowd. Nezam catches one. It is immediately snatched from his hand. He is ready to fight the thief, but it is an old woman in a black hijab. She uses the water to wash a steak-red baby before returning the bottle with a “Thank you.”

Nezam then snuck past the guards, claiming to be with a family waving blue passports. In the blast wall-lined holding area that separates the interior of the airport from the Taliban territory outside he finds the thief who took his backpack and thanked him for “Carrying it all this way.” When the thief protests, Nezam tells him he was Special Forces and a fight would get them both thrown out. The thief returns the backpack.

As soon as Nezam is inside the wire, the chat lights up with celebratory messages. A group member contacts his connection at the airport, who says they need a password for Nezam. The contact comes up with “Pineapple.”

The following scene might look like this in a movie

In Tampa, Scott falls to his knees in his driveway. His wife fears the worst until he looks up at her with a smile. “He made it, baby.” He changes chat room name from Team Nezam to Task Force Pineapple. Emojis of the fruit fly through the chat. The chat room fills up with names of other Afghans who need help getting through processing.

The work was only just beginning.

The Taliban’s Red Guard Unit keeps the field from being bombed by ISIS-K or rushed by civilians. With forty-sixty ISIS-K threats reported each day, everyone took extreme caution. The US forces guarding the gates give top priority to American citizens, green card holders, and lawful permanent residents. Nobody is going to grab a random Afghan commando with a SIV application.

Rahimi and his family try to gain entrance to HKIA again. This time a man is shot next to his wife. She faints. Rahimi has to carry her out of the crowd before she is trampled on. Once again, they return home. But unlike many around them, Rahimi is not giving up.

The chat is a war room of intelligence gathering and analytics. Everything was evolving at a breakneck pace. Original members return to their day jobs as new ones join.

Then someone asks about Nezam’s family.

Rising Obstacles (Pages 40-50)

This was the first time that Scott, who had not seen him in person for several years, had heard about Nezam having a family.

He quickly contacts him.

Nezam had been forced to marry by his corrupt uncle to claim his army salary. He and his wife have a daughter and two sons. He had put them on the SIV application, but they were never approved. Nezam had believed that they would be okay because the Taliban did not know about them. Scott tells him to have them taken to Liberty Gate. Nezam asks a male cousin to drive them the nine hours to HKIA. With the Taliban back in control, a woman traveling alone is taboo.

In the desert outside of Kabul Kazem buries a catch of weapons and sets the coordinates on his wristband GPS. We will return and kill those motherf—ers, he says to himself. On his way into Kabul to pick up his brother, he sees kids playing in an abandoned NDS vehicle, a .50 caliber machine mounted on the back. How could they disgrace Afghanistan this way? He calls Will Lyles. “Hey, boss, can you get me the [expletive] out of this place?”

Meanwhile, Scott boards a plane for Mount Sterling, Kentucky, to help his father in rehab after suffering a stroke. Even while traveling he makes Zoom calls that include people from every time zone in the United States.

The Taliban has captured government computers and had the names of every member of the Afghan Special Forces. Now they were searching for them. The members of the National Mine Removal Program (NMRG) knew the names and numbers of their American allies as well as their tactics, techniques, and procedures. It was an intelligence jackpot. Pineapple needed to exfil as many members of SF and NMRG as possible. Each member of Task Force Pineapple would be called a shepherd. They would all have flocks. Many flocks number in the dozens.

Scott looks at the cattle grazing peacefully on the lush Kentucky hills, in contrast with the storm raging in his head. People were asking a 50-year-old retired playwriter questions that only government officials could answer. With credible threats of an ISIS-K bombing, it made no sense that retirees were taking a mission meant for active special operators. It was an Uncle Sam-sized problem that the State Department and the Department of Defense should be handling.

He receives a call from a member of the task force. The operation was too chaotic. They need guys on the ground and Mann to take charge. The cavalry is not coming.

Mid-Point (Page 50-55)

Scott prepares to do something he put off years ago, TV interviews. The private sector’s response is overwhelming, with positive messages pouring in over Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger. One call is from a former Green Beret who had seen him on Fox. He and his buddies are ready to take over, identify threats and obstacles, plan for contingencies, and scale up operations.

After getting off the phone, Scott looks over at his father, a retired firefighter who has survived cancer twice and a stroke

“You guys are doing the right thing, Scotty,” his father says. “You don’t want to be on the wrong side of this. You’d never get over it.”

August 20: Abbey Gate is blocked off due to threats of IED attacks.

Jussi Tanner texts two women about their situation. They were next to the sewage canal. He sees the blue headscarves they had been instructed to wear. He asks the British soldiers to help him punch a hole in the wire. They cut a half-moon hole large enough for an adult to duck under. He motions to the women, who cross the sewage, climb over the retention wall with help from the British, and duck through the fence. Scott finds out about the secret entrance and sends the coordinates to Nezam’s wife. Neither Jussi nor Scott knew at the time just how many lives that half-moon-shaped gap in the fence would save.

August 21, Washington, D. C. Liv Gardener has barely slept in four days. She has not showered or done her hair. With her camera always off for Zoom meetings, she is unaware of her appearance. Her husband is completely behind her. “Just get as many people out as you can,” he tells her. She drops GPS pinpoints for Khalid, a former Afghan interpreter for U. S. Special Forces, into the group chat.

In Syracuse, Zac has had no success extracting Rahimi and his family through official channels, either military or political. He places a Hail Mary post on LinkedIn asking for help. The next morning while canoeing with his boys he checks his phone. Several former Green Berets and special forces veterans, including Jim Gant, the “Lawrance of Afghan” and mastermind of the VSO, have responded. They tell Zac about Task Force Pineapple which has just reunited an Afghan SOF named Nezam and his family before placing them on an outbound plane. They bring Zac into Pineapple’s chat room.

Rising Tenson (Pages 55-65)

In Kentucky, Scott receives a message asking for help rescuing an American citizen named Qais. He had worked as a contractor for the CIA, being a key component in exposing terrorist networks, before moved to the States in 2014 and starting restaurant. He had returned home for his sister’s wedding and been trapped by the sudden takeover. Since the Taliban had stuck a note on his door threatening his life over his work with the CIA, Qais needs the Americans to exfil his fourteen family members as well.

“An American citizen,” thought Mann. “This is getting out of control.”

On August 22 Sergeant Jesse Kennedy of the 82nd Airborne looks at the civilians lining the sewage canal. Men were kneed deep in the “sh*t trench.” One of them calls out to Jesse. His name is Khalid, and his pregnant wife needs help. Jesse checks his roster. There was no Khalid. The man named Khalid apologizes and says no problem, which Jesse finds odd.

Jesse thinks about what his deceased dad, who was always helping people worse off than them, would say about the situation. He decides take Khalid and his wife to a Norwegian field hospital. On the way, Khalid gives him his phone. The line is open to Liv Gardner with Congressman Mike Waltz on the line. Jesse thought he was fired. Instead, the congressman asks if he could handle more high-profile cases that needed exfil, including Khalid. “We’ll do what we can,” Jesse replies.

With Pineapple swelling to thirty-plus members, Scott tries to focus on his parents. But the situation in Afghanistan is all-consuming. Nezam had been a lucky break. The system could not save the hundreds that needed help right then and now.

Then he hears that Zac’s contact in the 82nd has said they are going to pack up and start a retrograde action in the next twenty-four hours. The Task Force is running out of time and ideas. With the US government in dereliction of duty, Pineapple needs a connection inside HKIA, even if it is a janitor.

Liv Gardner had someone.

Sergeant Jesse Kennedy.

When Nezam and his family land at an American base in Qatar, he sends Mann a message. Mann asks him for a picture of him and his family, safe and sound. Mann sends it through the chat to encourage everyone.

Meanwhile, Qais and his fourteen family members make it to a rallying point outside of HKIA. He is greeted by the Taliban, who refuse to let him pass and threaten to blow his head off even after he shows his passports. His contact with the State Department tells him to return home if he does not feel safe. After a Talib fires over his head, Qais takes his family out of the area. The idiots with the State Department had almost got us all killed.

Then he received a phone call from someone claiming to be with an NGO called Task Force Pineapple who was going to help him and his family get out. He doesn’t know what kind of Washington, D. C. bureaucratic b.s. is going on, but he and his family can’t return home. Not with terrorists after him.

On August 23rd, Zac comes up with a plan straight from his social studies classes. Operation Harriet is named after Harriet Tubman, the famous conductor of the Underground Railroad. He writes OP Harriet on a whiteboard. He lists each highly vetted Afghan heading a flock, the number of family members in each flock, then Plan, Pics, and Abbey Gate. Contacts on the ground would be “conductors.” The “underground railroad” would allow the Afghans to bypass the massive in-process line and mob at the gates. The flocks would come at night, wade across the sewage canal, then move through the hole in the fence that Jussi had made and go right on to processing at the State Department facility. Soldiers under Captain Folta would help the flocks cross the trench at pinpointed coordinates. He would text the information of each flock, names, number of members, and day of photos, on “baseball cards” to the contacts. The contacts would wear green glow sticks at the linkup point for the Afghans to identify the Americans. From there soldiers under Captain John Folta would take them to the airplanes. Zac makes these plans and moderates the situation via the television in a room with a floor covered in toy cars and bulldozers.

Scott returns to Tampa to meet the Green Berets who contacted him after his Fox News interview. A client of his is letting them use an office for the operation. While visiting he receives a call from Zac, informing him of Operation Harriet. He tells him how the paratroopers would look for iPhone screens with bright yellow graphics. “It worked in 1857. It should work in 2021, too.,” Zac assures. What else could they do in the face of unprecedented government inaction except treat it like a military operation, let their training kick in, and focus on the humanitarian task without getting involved in politics?

The first test subject for Operation Harriet is a former Afghan Special Forces operator, Al Salaam. He must trust his fate and that of his family in the hands of a man he has never met known only as Captain Zac. But he and the sixteen members of his flock follow the pinpoint drop to Abbey Gate. As darkness falls, they slip out of the crowd around the gate and past the Talibs calling anyone trying to leave the country traitors, men who a week ago Salaam had hunted without fear.

In Syracuse, Zac watches the news. He ponders the alternatives his Afghan allies have to face, sitting in the sun for days at the airport gates or being murdered in their homes by the terrorists. He sends text messages to Salaam, telling him to move through the canal toward the green light if he sees it. Salaam’s phone loses and regains signal. US and UN forces are using jammers to stop a potential IED attack. It looks like Operation Harriet is heading for failure.

Zac has not slept or washed in days. His wife Amanda can smell him from the next room as the ghosts of Afghanistan intrude into their lives. She checks her phone for the therapist’s number.

In Kabul, Saleem wades across the sewage. It takes him a few minutes, but he reaches the other side. He shows the paratroopers the yellow card on his phone. Captain Folta tells him to return and get his family. Soon the paratroopers have pulled sixteen Afghans out of the “sh*t trench.” Zac receives a picture of Saleem and the children inside the airport.

He lets out a whoop!

Operation Harriet is viable.

Zac smiles for a minute. Then gets back to work. Mohammad Rahimi and many more flocks still need guidance through the Underground Railroad.

Rising Tension / Obstacles (Pages 65-70)

As August 23rd draws to a close, First Sergeant Kennedy orders his men to begin packing their stuff. Loudspeakers warn the crowds outside the airport of Daesh – ISIS-K – mingling among them as the Taliban fires tracers over their heads.

On August 24th Scott receives a call from Will Lyles. He is having to do things on his phone that he once did in combat. He has not slept in days. His children cannot get his attention at the breakfast table. “We have to save Kazem,” he tells Scott, who brings him into Pineapple.

At Kabul, Kennedy and Folta return to the sewage trench. Despite warnings of a possible IED, word was that the underground railroad would be busier than usual that night. They come up with a new password: Seth Rogan, the actor from the movie Pineapple Express. The Americans would say “Seth.” The Afghans would reply, “Rogan.” John Rambo would have been easier for the Afghans to pronounce, but Rogan would have to do.

Mohammed Rahimi receives a “Go” message from Zac. His wife does not want to try again after she was almost shot the last time. The children have seen killings and other sights they should not have witnessed. “We must trust Mister Zac,” Rahimi tells her. Finally, she relents. The process takes them an hour until they are finally over the sewage ditch. “On the other side of that fence is the United States of America,” says Captain Folta, pointing toward the hole in the fence. Rahimi places the palm of his hand over his heart in appreciation.

The shepherds from across the states double-time their efforts to move their flocks into HKIA. Every time a message announces that a flock has reached safety, the chat fills with celebration. Then it was on to the next flock. New chats bury old ones within seconds.

Meanwhile, Scott helps his youngest son move into his college dorm. His wife says it is a big deal for their son, asking him to keep the Afghan calls to a minimum. Scott agrees, but then receives word that American Generals Miller and Donahue are blocking buses of Afghan commandos and their families from coming into HKIA. Miller says the SOF members need to be triaged. The Talibs are going door to door looking for the Green Beret’s SOF comrades using the data from the captured computer. Meanwhile, the CIA is airlifting the NSU paramilitaries out with their families. Nothing made sense.

Scott is so engrossed in expressing his frustration and anger that he doesn’t notice his son come out of his dorm room and catch him red-handed. When Scott gets off his phone, his wife Monty glares at him, balled fists on her hips. Quickly apologizing, Scott grabs his laptop. He and Task Force Pineapple need to keep pressure on US military and political officials.

Rising Action / Disaster (Pages 70-75)

They Have Seventy-Two Hours from U. S. Planes Going Wheels Up.

Qais complains to Task Force Pineapple about his mistreatment by the US government. Everyone is upset, but for now, they have to convince him to leave during the rapidly closing window. Qais refuses to leave unless every family member on the list is safe. Otherwise, they’ll all be killed. The members of Operation Pineapple understand. They would not leave without their families either.

Meanwhile, Kazem picks up his brother, Ahmed, and drives him to the airport in a stolen car he had hot-wired. After arriving at HKIA, Kazem and Ahmed are ordered away from the gates at gunpoint by U. S. soldiers. He contacts Will Lyles, who instructs him to hold up for the night. After shaving his beard so the Talibs cannot recognize him, he and his brother sleep in the stolen car outside the airport.

In Tampa, Scott’s inbox fills up with messages. People contact his non-profit, even his wife and kids, for help. It is no longer just Afghan SOF and interpreters, but women and girls at risk in the patriarchal Taliban society, that need help with SIVs or being manifested onto flights. He receives a call on his private cellphone from Vice President Kamala Harris’s office, which has officially said that there’s nothing that can be done about the humanitarian crisis, asking for help with getting some of her favored Afghans out of the country.

Meanwhile, the embassy’s local staff and families roll up to Liberty Gate and are ushered in through the CIA’s back door. The buses full of Afghan commandos and their families remain outside the wire. Some lost hope and got off the buses to return home.

August 26. The Signal chat is filled with GPS pindrops marking Taliban checkpoints while their foot patrols spread across the map of Kabul. Despite the time crunch, the shepherds move their flocks slowly to avoid the attraction of the Talibs.

Sleep is non-existent for Scott and the others in Operation Pineapple. He drinks from a Yeti mug filled with black coffee. But the success rate rises. In the first days of the operation, they had pulled in 130 Afghans. Now they were going for 600 in one night. A message appears in the chat regarding the US withdrawal. The window would close that evening at 5:00 p.m. Kabul time.

A movie could then have a scene like this showing the strain under which the operation put the families of the veterans.

At the airport, gates are welded shut because of the ISIS-K threat. Only Abbey Gate remains open.

In Kabul, Qais tells his fourteen family members this is the last time they are going to the airport. “We’re going to leave together or we’re to die together.” He shows them how to grab an AK-47 out of the hands of an opponent. His father urges him to leave with just his wife and children. “Don’t forgive me, father, – we’re leaving together,” Qais assures him.

In Syracuse Zac paces his kitchen. The express has been postponed from 8:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. Then pushed back to midnight. The darkness needed for the operation is burning up.

August 26 dawns with word that not one of the six hundred Afghans has crossed into HKIA. The contacts in the 82nd had been pulled away from the linkup point for seven hours. The Taliban now has all roads blocked, and gates were being walled up to deter the ever-increasing ISIS-K threat.

Operation Pineapple extends its timeline as communication keeps going in and out due to jammers and the Taliban destroying local cell towers. Jussi Tanner watches as a NATO soldier in a field of abandoned UN vests smashes abandoned blue helmets with a hammer. This can’t last much longer; he thinks to himself.

5:30 am Kabul time. Conductors are still not in place, but contacts assure Zac Pineapple Express will soon be back up. The shepherds keep doing their job. In Washington, D. C., Liv Gardner looks at the words on her ceramic cup: Coffee – You Can Sleep When You’re Dead. So true. She reads off a prep talk on how to keep the flocks motivated. Remind them of their future, and their children’s futures.

Now that the NEO – Noncombat Evacuation Operation – is wrapping up, the ISIS-K threat rises higher. At 7:07 the U. S. Embassy alerts citizens to immediately leave Abbey, East, and North gates.

In Tampa, Scott battles an old ghost after hearing that a six-year-old girl has been trampled to death. He comes to terms that it was better than being raped, enslaved, and seeing her parents killed by the Taliban. Another family gave up after their two-year-old nearly drowned in the sewage. Scott tells himself he doesn’t have the right to be tired. The Afghans have waited at the airport for days without food, some with no water for twenty hours.

In Kabul, Captain Folta needs a codename. He puts on red shades and becomes Captain Sunglasses. He walks up and down the canal checking the “baseball cards” on his phone. When he recognizes a flock leader, he asks how many are in his group. If the flock leader responds correctly, he pulls him and his flock out of the trench with the help of British officers who are also looking for Pineapples.

But flocks are still giving up and returning home. Shepherds receive videos of Afghans who were captured and executed by the Taliban after finding the Americans’ numbers on their phones. Some shepherds listen live in horror as their allies, almost to the gates of KHIA, are murdered in daylight by Talibs. Scott swears and slams his fist into his oak desk. They need to pull out all stops and network with as many military contacts along the perimeter as possible.

Kabal, 12:45 P. M. Qais’ contact looks at his watch. It’s 4:15 A.M. in America. Qais and his family have been there since 3:00 am. They should have been picked up two hours ago. The contact tells Qais to walk to Liberty Gate. Maybe he can be extracted as a “special case.” Other shepherds are sent to the sewage canal, a key element on the “underground railroad” because the Talibs will not go near the smell. The flocks can get tetanus shots later.

Qais’s contact tracks his progress to Liberty Gate. He sends him a selfie of his on-ground conductor, a Ranger, with a full-color American flag patch on his vest, who should meet him at North Gate. Qais and his family start moving at 3:30.

At 3:40 p.m. a message goes through the group chat that US and allied military operations may end indefinitely at 1700 hours. The 82nd will start moving out the next day. Finally, at 7:42, Qais texts that he and his family – all fourteen – were safely inside the wire.

Climax of Act II (Pages 75-80)

Kazem and his brother sludge through the sewage. Nearby a woman gives birth in the dirt for all to see. People yell “Pineapple!” or “Rogan!” all around him. Some yell because those words worked for others. Many of them have the same pineapple graphics on their phones as Kazem has on his. A sh*t storm in a sh*t trench, he thinks to himself.

Then he sees the big red shades. It’s Captain Red Sunglasses.

A movie would then switch to Houston, Texas with a screen like this

4:35 pm. A woman named June who works with at-risk girls in Afghanistan sends a message to the chat room. She needs help with a group of girls from a music school. Scott is shaving, about to meet his wife at a car dealership. He looks in the mirror at the face that Afghanistan had aged. Maybe one last chance, He thinks to himself. On the way to the dealership, he has to stop and pull over to read messages and deal with the details.

5:33 p.m. Zac sends a message: Only 30 minutes left!

C-17s roar over the airport, taking off every few minutes. One of the last ones out carries Kazem, alone. He has been forced to leave his brother behind by a skeptical young American soldier during processing.

Folta and his men pack up. So far that day they had pulled out 330 people. The Marines have kept Abbey Gate open a little past 1700 hours but are about to shut it down.

5:48 p.m. Jesse Kennedy and his paratroopers move through a concrete alleyway leading to a hole in the blast wall. Suddenly he hears a blast. He looks up and sees a mushroom cloud of smoke behind the blast wall.

End of Act II – All Is Lost

Act III

An ISIS-K bomber has detonated his vest, sending ball bearings through the densely packed crowd. Scores are injured and nearly 200 were killed. Among the dead are 13 American servicemen and women.

Marine Corps Lance Cpl. David L. Espinoza, 20

Marine Corps Sgt. Nicole L. Gee, 23

Marine Corps Staff Sgt. Darin T. Hoover, 31

Army Staff Sgt. Ryan C. Knauss, 23

Marine Corps Cpl. Hunter Lopez, 22

Marine Corps Lance Cpl. Rylee J. McCollum, 20

Marine Corps Lance Cpl. Dylan R. Merola, 20

Marine Corps Lance Cpl. Kareem M. Nikoui, 20

Marine Corps Sgt. Johanny Rosario Pichardo, 25

Marine Corps Cpl. Humberto A. Sanchez, 22

Marine Corps Lance Cpl. Jared M. Schmitz, 20

Navy Hospital Corpsman Maxton W. Soviak, 22

Marine Corps Cpl. Daegan W. Page, 23

They were the first American combat casualties in Afghanistan in 17 months.

Reports of an IED explosion at Abbey Gate fill the Pineapple chat. The explosion occurred behind a small wall just across the road from the sewage trench. There are reports of bodies in the canal.

Descending Action (Pages 75-80)

At the Kabul airport, it is a scene straight out of Schindler’s List. Jussi Tanner works in the makeshift hospital. He sees a girl no more than ten years old in a light red dress. The bottom is a darker shade than the top. He later asks a medic about her. The medic shakes their head.

That evening Ambassador Ross Wilson and Major General Chris Donahue take part in a flag-folding ceremony.

On August 28 Scott contacts June about the school-aged orphans. As far as she can tell they did not make it. But she tells him to take solace in that Task Force Pineapple gave them something they did not have: Hope.

The Biden administration tries to save face after the suicide bombing by ordering a drone strike on August 29. It kills ten innocent Afghans, including seven children.

At HKIA All the gates are welded shut. Sand and chemicals are poured into the fuel tanks of planes and helicopters so they cannot fly. The last flight takes off on August 30th. Some of the last boots off the ground are Jesse Kenndy and John Folta.

Resolution (Pages 85-90)

Having rescued 1,000 Afghans, Scott, Liv, Zac, and the other members of Task Force Pineapple return as best they can to normal life in America. They make amends with and focus on their families. In September Scott is asked to meet with The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley. The chairman calls the American airlift, Operation Allies Refuge, the “greatest airlift in American history. Over a hundred twenty-five thousand Americans and Afghans were lifted out. It is unprecedented!”

Scott knows political theater and damage control when he sees it. The airlift was also the greatest betrayal of America’s allies. People left on rental buses or denied entrance at the gates. Allies killed by the Taliban and ISIS-K just a few feet from freedom.

Milley wants Mann’s help with a private-public task force to get more Afghans out using private groups like Pineapple. Scott asks if there are to be Department of Defense assets for the project. Milley says the DoD will not commit assets. The State Department would be in support. There was the truth of the matter. And Scott wants nothing to do with it.

On his flight home, he thinks about the six thousand Afghans remaining on Pineapple’s manifest, without a lifeline to the outside world. Many will be hunted, captured, or killed by the Taliban and other terrorists without his help. By the time he arrives in Tampa, his mind is made up. Task Force Pineapple was going to play the long game. They would continue to extract Afghans as a private group.

Private groups like Pineapple extracted at least 125,000 allies out of Afghanistan during its fall. Mohammad Rahimi settles in Syracuse with the help of Zac. He finds American TV too violent to watch with his traumatized son. Kazem takes up residence in Durham, North Carolina. “This country is all about having nice things,” he tells Will Lyles one day. He returns to Afghanistan, his motto changed from “Life [Expletive] Sucks” to “Live to Fight Another Day.”

In Tampa, Scott and Nezam sit around a campfire. They watch their families mingle, prepare food, and play together. Nezam watches two of his children present Scott with carefully drawn pictures of the American flag. Scott hugs them in thanks.

The Backpack Man has found a home.

Final Thoughts

General Milley refused calls to resign despite the thousands left behind. Scott Mann writes that “Over the course of its history, America had liberated Nazi concentration camps, pulled off the Berlin Airlift, and delivered aid to disaster-struck countries across the globe. To claim victory in the events that occurred in Afghanistan belies the purpose of the airlift in the first place, which was to save American citizens and at-risk Afghans from the violence of the Taliban.” I would add that after a century of US Military and Government aid and operations, from the Armenian Genocide and the Burning of Smyrna to the evacuation of Hungnam during the Korean War, to the fall of Saigon, to the rescue of the Kurds in 1996 and the Yazidis in 2014, there is a rich history that our leaders could have drawn from to plan for the evacuation. Additionally, studies show how fast Western-backed governments fall after their support is withdrawn, often within a month or two. That the Biden Administration did not take any of this into account, did not leave support for Afghanistan’s air assets, have emergency operations personnel or aircraft on standby, or send troops in to widen the perimeter around the airport should be considered criminally negligent. Operation Pineapple Express Should Be A Movie That Holds Our Government, Both Republican and Democrat, Accountable.

The actions by the US government have created a national security risk. US-trained commandos may join forces with ISIS-K to avenge their betrayal. The abandonment surrendered twenty years of network, slowly built relationships, and intertribal and cross-cultural diplomacy – “Strategic Social Capital” – in the blink of an eye. As Mann learned during his tours in Afghanistan, we cannot kill to victory in the War on Terror. Relationships with local and indigenous partner forces are essential to a war that is “fought in the shadows.” A key weapon in his strategy is trust and commitment to one’s word, a promise. Operation Pineapple Express Should Be A Movie To Help Americans Understand That While Navy SEAL Raids Are Flashy, It is Ultimately Relationships Established By Special Forces like the Green Berets That Will Win The War on Terror.

As a result of Washington canceling the promise made by Green Berets and other military personnel, the military community has experienced a mental health crisis. Suicide rates doubled. What was the point of all the blood and toil, 2,459 American lives, if after twenty years it was allowed to just collapse at the end? Mental health hotlines for veterans were overloaded during the withdrawal as they saw their service to their country betrayed by their government. One Green Beret feels like instead of liberating the oppressed, their government oppressed the liberated. To Honor These Betrayed Veterans Who, In An Age of Extreme Egalitarianism, And Having No Legal Obligation, Honored Their Sacred Promises And Returned To Rescue Their Allies Is A Reason Operation Pineapple Express Should Be A Movie.

As of the writing of Mann’s book, (August 2022), 25,000 Afghan Special Operation Forces and aviators were trapped and hunted by the Taliban along with thousands of legitimate SIV applicants. 20,000 Afghan soldiers who fought to the last bullet as their government collapsed were left behind as they did not have time to fill out applications. Many face starvation since going to the village elders for rations would expose them to the system now run by the Taliban government. Every day the veterans who went above and beyond their duty to rescue their allies think of those who did not make it out. Other volunteer organizations like Operation Pineapple helping those who remain behind include Operation Dunkirk, Sacred Promise, Team America, Aghan Free, Afghan Evac, Save Our Allies, Project Dynamo, Project Exodus Relief, Moral Compass, and Team America Relief. Once again, no matter how shamefully the American government may fail, the American people’s spirit, generosity, and resilience triumph.

The rescue work continues in the shadows.

To raise awareness of the issues still facing our allies in Afghanistan and those helping them, hold our government accountable, and honor our betrayed veterans of the Afghan War who went above and beyond the call of duty is why Operation Pineapple Express by Scott Mann Should Be A Movie.